Embracing complexity in Human-Wildlife Coexistence

In landscapes where people and wildlife must share space, simplistic solutions like electric fences or compensation schemes often fail to address the deeper causes of human-wildlife conflict. A recent study by Kansky, Riechers, and Fischer, based on over six years of research in Namibia's Zambezi Region, makes a compelling case: to achieve meaningful coexistence, we must embrace - not ignore - the complexity of human-wildlife systems.

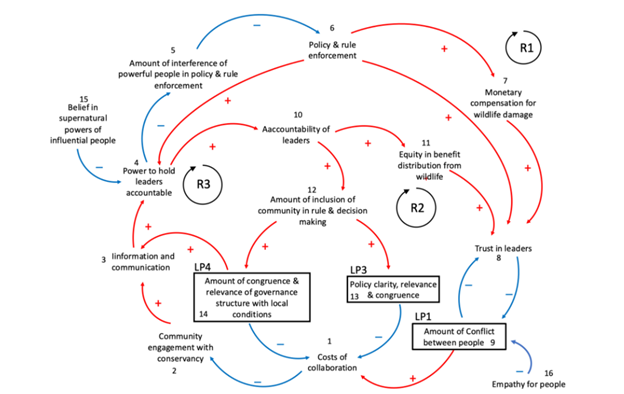

The authors turned used causal loop diagrams (CLDs) and a leverage points perspective to visualize the intricate complexity of social, ecological, and institutional dynamics. Mapping 32 variables and 47 relationships across two subsystems - governance and wildlife - they uncovered reinforcing feedback loops that trap communities in cycles of mistrust, weak accountability, low tolerance for wildlife, and underperforming conservation outcomes.

Considering this complexity, the researchers identified four strategic leverage points where well-placed interventions could create lasting systemic change:

- Conflict between people

- Human tolerance for wildlife

- Policy clarity and relevance

- Governance structures aligned with local realities

What stood out most was the effectiveness of social learning programs: community-based workshops grounded in nonviolent communication, systems thinking, and governance innovation. These programs not only nurtured empathy and improved leadership, but also helped participants engage with policy in meaningful ways and co-develop practical solutions.

Figure taken from Kansky et al. (2025)

Relevance for SESCARNIVORE

The insights from this study are especially relevant to our SESCARNIVORE project, which seeks to foster sustainable coexistence with large carnivores across Europe. Much like the Zambezi case, the regions targeted by SESCARNIVORE face growing tensions between large carnivore conservation goals and livelihoods. By applying systems thinking and participatory approaches, SESCARNIVORE can more effectively tackle root causes of conflict rather than symptoms, and design interventions that resonate with local realities.

In short, the study by Kansky and colleagues provides both a conceptual framework and practical tools that can inform and strengthen SESCARNIVORE's mission to transform carnivore conservation from a source of tension into a foundation for collaborative, adaptive, and just coexistence.